Our Heroes

I had breakfast recently with two of my oldest and closest friends. The conversation turned to baseball and our being thankful for growing up in Cincinnati during the Big Red Machine era. We talked about meeting some of those Reds stars in person, mostly good but a couple bad experiences. My one friend reflected on advice given to him by his father years ago: “Don’t idolize them for anything other than their play on the field. You just never know what their personal lives might be like.” With the news of Wander Franco being placed on administrative leave this past week, that remains sound advice. Let’s take a look at some events in baseball history that put our baseball idols into hot water.

In the early part of the 20th century, scandals surrounded a couple of the all-time greatest baseball players. The 1919 World Series will forever be remembered by the Black Sox Scandal. Shoeless Joe Jackson and seven other Sox players were accused of throwing the Series by accepting bribes and indicted for a conspiracy to defraud the public. While the players were eventually acquitted, they were suspended for life by Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis. Ty Cobb, who clearly is in the top five of baseball greats, had his legacy marred by allegations of racism and violence, much of which has been discredited. Yet, most every accounting of Cobb’s contributions to baseball ends on that sour note.

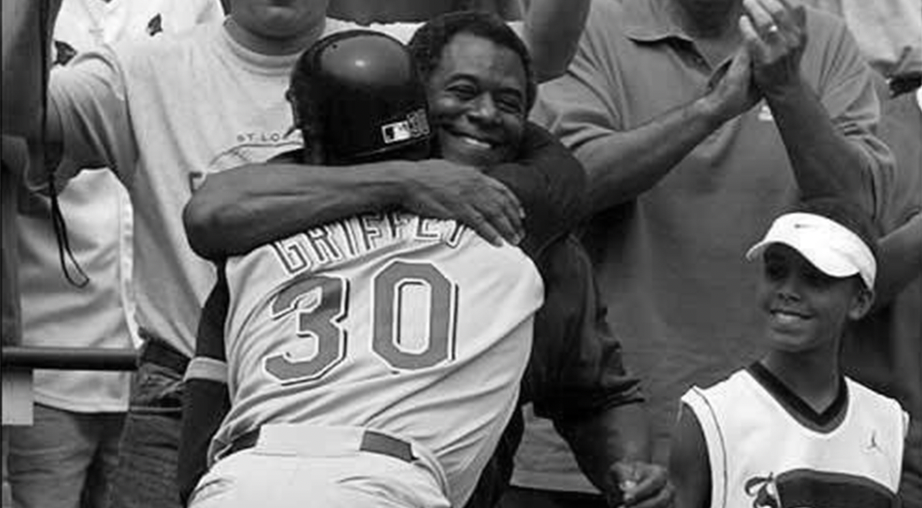

Prior to the 1947 season Brooklyn Dodgers manager Leo Durocher was suspended for one year for associating with gambling figures. You remember the 1947 season -- Dodger great Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier. Durocher was a huge supporter of Robinson but couldn’t be there for him. A decade later, two other New York baseball legends were introduced, the New York Giants’ Willie Mays and the Yankees’ Mickey Mantle. Both were the epitome of five-tool players, and their career numbers demonstrated it. Yet, after both players had been inducted into the Hall of Fame, Commissioner Bowie Kuhn gave them life bans from baseball for essentially hanging out at casinos. Peter Ueberroth lifted the bans as one of his first acts as Commissioner.

Gambling took center stage at the end of Pete Rose’s great career. MLB’s all-time hit leader returned to the Reds in 1984 as player manager and retired from the playing field two years later. In August 1989 a story broke that Rose gambled on baseball games while he played for and managed the Reds. He was placed on the permanent ineligibility list. In 1991, the Hall of Fame voted to ban players on the permanent ineligibility list from induction.

This particular scandal hit me hard. I idolized Pete growing up, a player from my side of town in Cincinnati who willed himself to become one of the best ever. I recall Marty Brennaman, Reds’ longtime radio announcer, defending Rose on the airwaves. I so hoped that Brenneman was correct and the allegations were not true. After twenty years of denial, Rose admitted in 2004 to gambling on baseball and on his Reds. And unfortunately, we most likely never will see his plaque in the Hall of Fame.

In the 1990s I recall driving to work each morning and listening to radio reports of the top ten home runs hit the night before. I knew something was up, but couldn’t imagine the extent of steroid use by players at that time. As a baseball fan or anyone following sports, it is impossible to forget the 1998 home run race between Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa or the record-shattering year by Barry Bonds in 2001. In 2007, United States Senator George Mitchell issued a lengthy report on baseball’s so-called “Steroid Era”, putting the names of McGwire, Sosa, Bonds, Roger Clemens, and many more in a light that forever dims their careers.

More recently, the 2017 World Series will always have a black eye due to the Astros’ cheating scandal. In 2019 The Athletic disclosed an investigation that Houston had used a camera to steal signs from opponents at home games during the 2017 season. More and more information about the cheating came out, including my favorite, Astros players banging on trash cans to signal their teammates about pitches. While Commissioner Manfred suspended GM Jeff Luhnow and manager A.J. Linch for one year, not a single player was disciplined. I don’t know about you, but I’ll never forgive the players involved. Their reputations are severely damaged.

On August 14 Tampa Rays star Wander Franco was placed on the restricted list as MLB launched an investigation into social media reports that he was in a relationship with a minor. After a week of inquiry, MLB placed him on administrative leave indefinitely. The reports are that prosecutors in the Dominican Republic are investigating Franco under a division specializing in minors and gender violence. It is very sad for all involved – the victim of the alleged act, Franco, the Rays, Rays fans, and baseball.

Having baseball idols is a fun part of life. When they shatter their images, you have to remember the advice of my friend’s dad -- separate the baseball and personal lives. When I was about twelve, I purchased Ball Four, a book written by Yankees pitcher Jim Bouton giving an inside look at baseball players at the time. It was pretty scandalous, detailing obscene jokes and routine drug use. About halfway through my read, the book disappeared from my room. I asked my Dad about it, and he said he would give it back to me when I was ready for it. The book was never returned. Perhaps my own Dad’s advice was the same as my friend’s dad, maybe you just don’t want to know.

Until next Monday,

your Baseball Bench Coach